Re-formations of the Reformation

A Hunt for Recycled Altar Stones in Lincolnshire

During the half term holiday in February 2019 I took my children to Lincolnshire to see if we could find any altar stones removed from parish churches in the 1560s during the mature stages of the English Reformation.

In 1566 Lincolnshire parishes returned an ‘Inventory of Monuments of Superstition’ which recorded the fate of ‘popish ornaments’ taken from the churches and often defaced, destroyed, reused or sold. Altar stones were the least portable of these ecclesiastical items. Some repaved church floors, some were used to form parts of village bridges, some became stepping stones, stairs, sinks or cisterns. They can be hunted near old parish churches, often downhill at nearby streams.

On the first day we explored Kirton-in-Lindsey and Northorpe. In Kirton-in-Lindsey an original altar stone has been restored to use in the church, after being redeployed as a threshold during the Reformation. It was found in 1936 beneath the tower, replete with graffiti from eighteenth century.

Credit: Maud Webster

An effigy of a knight, rediscovered in 1862, has also been restored to a position within the church after lying concealed under the floor for centuries (The 800 Year Old History of St Andrew’s Church, Kirton-in-Lindsey):

Credit: Maud Webster

The church in Northorpe was locked, confounding our attempts to view the brass inscribed to Anthony Monson, who died in 1648, which is embedded in a medieval altar stone that features five consecration crosses:

Memorial brass, St John the Baptist church, Northorpe

Credit: © Julian P Guffogg - geograph.org.uk/p/5395908 - cc-by-sa/2.0

Northorpe Church, Lincolnshire

Credit: Maud Webster

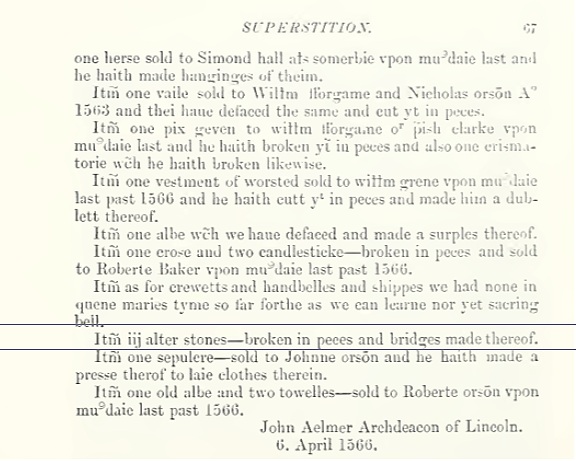

The second day of adventuring took us to Denton, Kelby and Lower Bitchfield. The 1566 returns for Denton tell us that the three altar stones had been broken up to make bridges:

From Edward Peacock, English Church Furniture (London, 1866)

That had us looking for the nearest water crossing to the church, clambering through undergrowth, and almost falling in. We identified a few possible altar pieces, but with no real confidence – we didn’t find any consecration crosses.

Next stop was Kelby, where we sought parts of two altar stones which had been ‘defacid and laid in high waies and serveth as bridges for sheep and cattall to go on’:

Again, we found various bits of stone which could be altar stones but no solid evidence. In such things it is rarely possible to be conclusive. This flat stone forms part of what appears to be part of an old bridge (the stream has since dried up but the structure is still used as a crossing for animals):

Possible altar stone in an old bridge near Kelby, Lincolnshire

Credit: Maud Webster

From his perch on Kelby Church, a gargoyle seems to mock our efforts.

From Kelby we set off for our final destination in Lower Bitchfield, its name a cause of much amusement as we drove in and out of it repeatedly, trying to find our way. We searched (in vain) for parts of three altar stones, two of which were used to bear up the bank on ‘brod bridge’. The third was broken up and defaced in 1565:

Accidentally dressed as a ghoul, below I examine a tomb outside the Church of St Mary Magdalene, Lower Bitchfield. Some altar stones were used to top such tombs, but not this one.

I thought my children would be disappointed that we had not entirely succeeded in our mission to find the promised altar stones. The mission had involved a lot of driving in circles through Lincolnshire and lacked the certainty and glamour favoured by the curriculum. But in fact they both expressed surprise that the study of history could involve poking around old bridges, along the banks of forgotten streams. At times they thrilled to the thought that we may have been the first to go looking for these relics since they suddenly lost their magic all those centuries ago.